How many times have we all heard or read phrases like you must use a full range of motion, go all the way down, lock out at the top, touch the bar to your chest, ass to grass, partial range equals partial development, and the list goes on.

To maximize muscle hypertrophy and development yes you need to take the muscle through its full range of motion in order to recruit all available motor units. In other words, you should train it from the fully lengthened to the fully shortened position. Most experts will agree on that.

However, it is important to make a critical distinction between taking a muscle through its full range vs taking an exercise through its full range in the context of hypertrophy development.

No single exercise will overload a muscle maximally through its entire range of motion. Let me repeat that so it sinks. “No one exercise will overload a muscle maximally through its entire range of motion.”

Any given exercise will typically overload a muscle in the middle, bottom or top position of the strength curve based on where the tension is highest.

For example, compounds movements like bench presses and squats primarily overload the middle range. If we analyze the Squat biomechanically, we can deduct that torque is highest in the middle when the thigh is parallel to the ground and the lever is longest.

Since tension in the muscle is proportional to the torque and tension is the key trigger for hypertrophy, it stands to reason that those exercises offer the greatest muscle-building stimuli in the middle range.

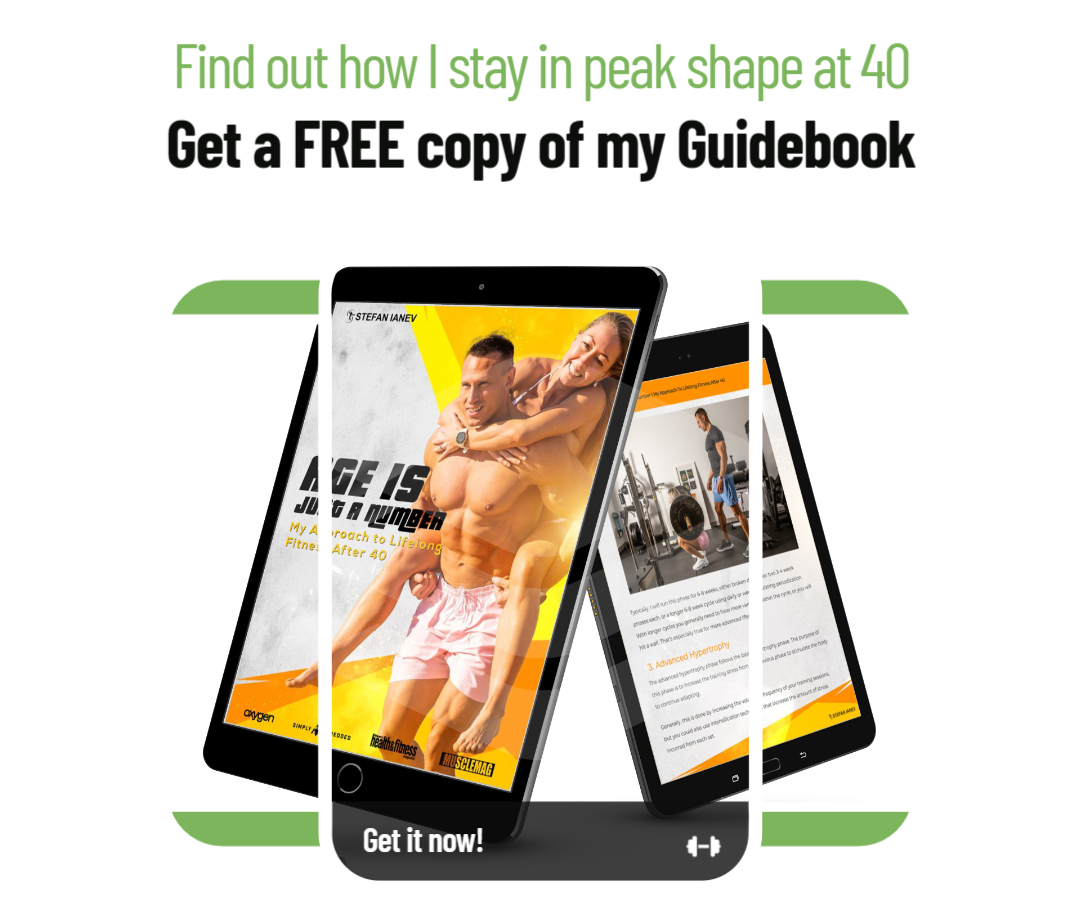

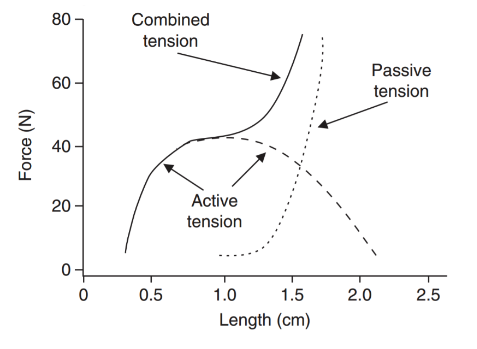

However, this is where things start to get tricky since we need to distinguish between active tension and passive tension. The active tension a muscle fiber produces is determined by the degree of overlap between the actin and myosin filaments, which affects how many crossbridges can form.

Peak active tension occurs near the resting length of a muscle fiber where the actin and myosin filaments are neither too bundled up or spaced too far apart (1,2).

This is shown in the following graph from Power (1).

The passive tension a muscle fiber produces is determined by the stretch of the elastic structural elements inside the fiber, such as the cell cytoskeleton, titin, and the surrounding collagen layer of the fiber, called the endomysium. Passive tension increases exponentially as a muscle fiber is stretched to longer lengths (2).

This is demonstrated in the following graph from Brughelli and Cronin (2).

When a muscle fiber produces a large contractile force with its passive elements, it deforms longitudinally, which stimulates the fiber to increase in length. When a muscle fiber produces a large contractile force with its active elements, it bulges outwards, which stimulates the fiber to increase in diameter (3).

That is why both full squats and half squats can be effective for increasing hypertrophy by stimulating the muscle fibers in different ways. Half squats allow you to overload the active elements of a muscle fiber with a greater load, while full squats allow you to overload the passive elements by stretching the muscles under load. Both produce high tension on the muscle fibers but one is more active tension while the other is more passive tension.

Overall, stretching the muscles under load produces the highest combined tension as was shown previously in the graph by Brughelli and Cronin (2). Therefore, full squats would be the preferred option if you could only do one squat variation, however, adding in half squats can be effective for increasing active tension and stimulating the belly of the muscle to a greater degree.

Alternatively, you could perform half squats to maximize active tension, then use another exercise such as sissy squats to maximize passive tension where the muscle is maximally stretched under load. Theoretically, that would offer the greatest muscle building benefit since both active and passive tension are being maximized.

What about exercise in which tension is highest at the top of the movement like dumbbell lat raises i.e. exercise with a descending strength curve?

Typically, in exercises with a descending strength curve there is no passive tension, and the active tension at the top of the movement is not maximal because the actin and myosin filaments are too overlapped to generate maximal force.

That is not to say exercises with a descending strength curve should not be used at all. They are effective for increasing the mind-to-muscle connection for muscle groups that are less neurologically efficient. They also usually cause less joint stress, so they can be useful for unloading the joints. However, they are generally not going to create as much mechanical loading as exercises with an ascending or a bell strength curve, where most of the tension is at the bottom or the middle of the movement.

References

Power GA. “Neuromuscular Function Following Lengthening Contractions.” (2012).

Brughelli M, Cronin J. Altering the length-tension relationship with eccentric exercise : implications for performance and injury. Sports Med. 2007;37(9):807-26. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737090-00004. PMID: 17722950.

Valamatos MJ, Tavares F, Santos RM, Veloso AP, Mil-Homens P. Influence of full range of motion vs. equalized partial range of motion training on muscle architecture and mechanical properties. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2018;118(9):1969-1983. doi:10.1007/s00421-018-3932-x